Archives, instability and plant extinction

This is a text performance written for the 5th EDITION of ARCHIVAL PRACTICES IN CONTEMPORARY VISUAL ARTS, hosted by Archivo, in 2024. The text was accompanied by a moving image work.

This is a story about endings.

About climate change and the 500-fold increase in plant extinctions.

About archival traces and reckonings.

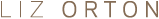

One of its beginnings, for me, is in 2012 when I was a visiting artist at Kew Gardens herbarium. As usual I was lost among the rows of cupboards housing millions of plant specimens. I was a body without a method, wandering, and largely ignorant of the taxonomic cuts and divisions that organise the herbarium by to class and family, genus, species, subspecies.

I was looking for signs of weakness or fallibility in this formidable system. When anyone asked me what I was doing I said I would let them know when I knew. I was an unstable force, and did not seem impressive.

One day, a botanist, with the visionary name of Dr Flowers, showed me a specimen of an Orbilex Stipulatum, from Rock Island near Ohio Falls, dated 1842. ‘It was known locally as rock cress’, she said, ‘but it’s extinct now, and this is the last specimen of the species ever collected.’ Sometimes, a herbarium specimen is the only evidence that a species existed at all.

I thought of a faded family photograph, for which the negative has been lost, its relationship to the original event almost broken. A document straining to hold on to that which is lost.

Herbarium specimens, like photographs, are a record of time passing, a snapshot in a long and ever-changing evolutionary narrative. It is possible to deduce the environmental conditions that once existed at a place based only on the knowledge of the plants that used to live there. Plants are witnesses to environmental change, chlorophyllic archives that store accumulated evidence of pollution, migration, war, climate and temperature change.

The herbarium protects against what scientists refer to shifting baseline syndrome, our tendency to imagine that the environmental conditions at the edge of our own memories are the way the world has always been.

Soon after my conversation with Dr Flowers I joined a search for Epipogium aphyllum, known commonly as the Ghost Orchid. Orchids are an indicator species, a sign of wider ecosystem health. The first recorded sighting of the ghost orchid in the UK was in 1854 and it has only been seen a handful of times since, most recently in 2009, in a location that is a closely kept secret. It wasn’t seen at all for 70 years from 1910, only to appear in 1982.

It is listed as critically endangered and possibly extinct.

We left London for Buckinghamshire by train early one morning, and shared a quiet and serious cab ride to a nearby area of woodland. I was the only non-botanist and checked my pocket frequently for my picture of the flower, its pale, floating, phantom-like petals suspended in the air.

The leader of the search divided key areas of the wood into invisible grids that we were to keep mapped in our heads. Ghost Orchids don’t need light to survive, so he directed us towards the darkest parts of the wood. There was a light drizzle as 8 of swept across the forest floor poking at the leaf litter, bending again and again, sometimes crawling.

We barely talk, our bodies making a wet dance that only stops when it starts to get dark.

I was disappointed but also relieved not to find the ghost because I believe in nature’s right not to be seen.

Extinction has been called a hyper-object, a phenomenon of such vast scale and so enduring, that it can’t be understood in any traditional sense, using sight or touch or smell. Evidence of hyper objects comes in fragments, that, according to Timothy Morton, “clip in and out of our vision like malevolent ghosts.”[1]

Images of orchids and other extinct plants become my ghosts.

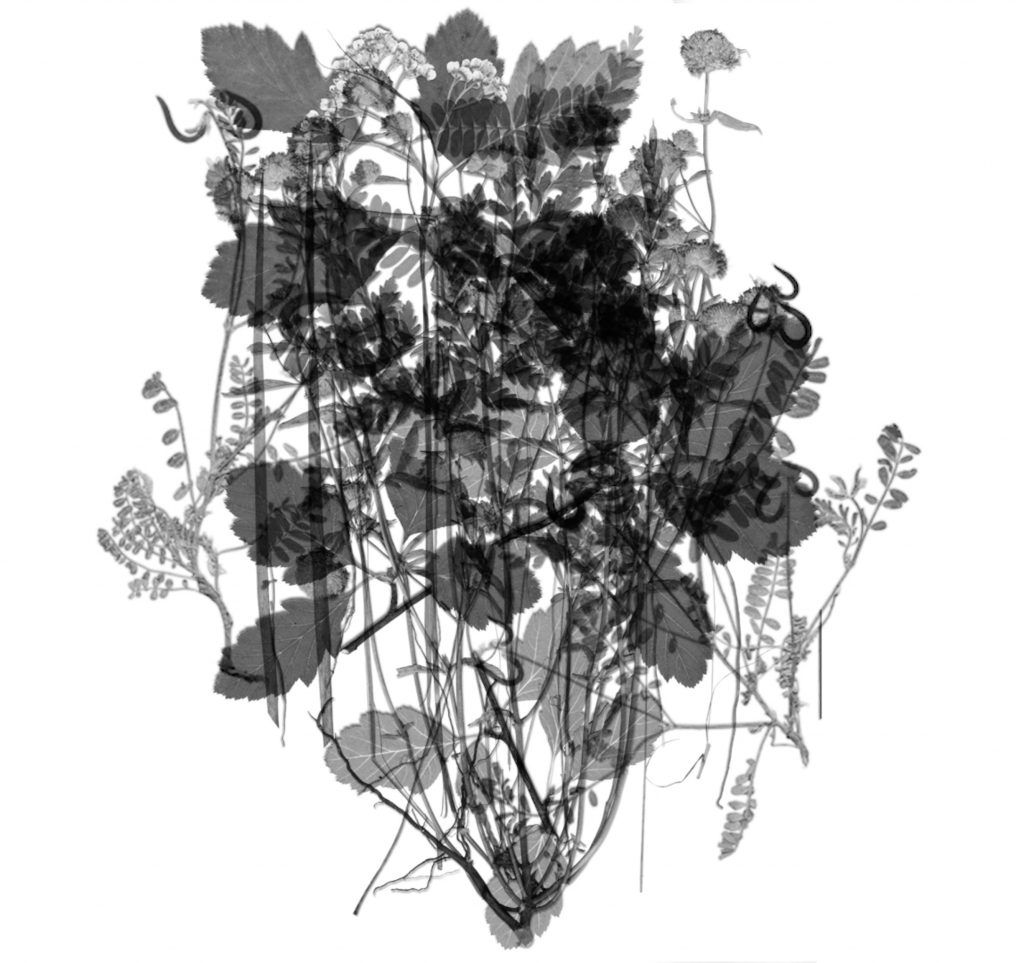

Botany turns nature into specimens, fixing the plant like an image, on the white, with a capital W, paper of the herbarium sheet. Photography completes this process of image-making.[2] At Kew herbarium 5.4 million specimens have been photographed to create a digital archive tagged by species name, date, location, habitat information, and collector name. Photography is the perfect companion to botany with its histories of categorisation, hierarchisation and classification.

The digital archive isn’t a mirror or a reproduction of the herbarium, just as the herbarium is not a copy of nature. Digitisation enacts a rupture, between the specimen and the image; between originality and reproduction, between then and now. It multiplies images and audiences and opens up new forms of comparison and computation, creating algorithmic knowledge that is a new resource for conservation. But when the database shapes the world in its image, we must ask what knowledge and for whom?

My residency at Kew comes to an end but I have the logins, to digital Kew and other herbaria and I escalate my search for extinct plants online.

Free from the structures of the physical herbarium and its necessities for prior knowledge I can make my own digital collections, incisions that cut across established taxonomies and orders. I find 325 species in 27 countries named by or after George Forrest, a Scottish colonial botanist who lived from 1873 to 1932. And four species from a small region in Norway where my great grandmother lived. I find three specimens of amomum verum, the first species to be named by a woman, but which has now been re-named.

But there is no methodology for dying. Extinction, is not a search term.

So I tune in elsewhere, to redlists and journals and micro databases. And listen for the continued vibrations of the specimens and their images.

I struggle to match up information from many the different sources. In 2013 I find just four images of extinct plants, with their Latin names.

In landscape the loss of a plant species often goes unnoticed, the slow systemic violence of industrialisation, urbanisation, tourism, war and climate change grinding relentlessly on, the losses quietly accumulating. The website of The International Union for Conservation of Nature lists the demise of hundreds of thousands of species. I read descriptions of critically endangered plants, some with as few as one or two mature individuals. Plants go extinct quietly only because we don’t make enough noise about it.

The extinction of the last individual plant is always more than the death of a species, it is the end of entire ways and forms of life. Relationships unravel, dependencies and mutualities falter and worlds of knowledge and practice fade away. [3]

In 2014 to 2015, I find 12 images of extinct plants and 2 critically endangered plants because these are the extinctions to come, reminders that we live in an urgent present.

Archival time, digital time, ecological time, and life time all have different seasons, different measures. They overlap and diverge.

I go back to the woods and search again for the Ghost Orchid, not because I want to find it but to feel the experience of not knowing. How do we prove that something no longer exists? Ghost Orchids hardly ever appear in the same place twice and can go for as long as thirty years without flowering at all. Only a single sighting would bring it back from extinction. Holding the image of the ghost in my mind this time I abandon the discipline of the first search, and let myself be led by the forest, following its patterns of light and shade, and the dip and weave of its leafy ground.

Deborah Rose has called extinction a double death, the end of a lineage cultivated over hundreds of thousands, perhaps even millions of years, and the extinction of times to come. It is a question to us who still remain, how we hold open the future by paying attention to the ghosts of the past. [4]

In 2016 I find 20 images of extinct and 12 critically endangered plants. I also find 25 common plant names in local languages.

Local names hold cultural and ecological knowledge. Knowledge that colonial botany disregarded when it ignored local names in favour of its Latin naming system, using language to help secure its hold on nature and its resources.

Plant names are more than labels. They can embody a history, a sense of place and a right to belong. They are part of ecosystems. So linguistic violence is cultural, environmental and political violence too.

I email botanists around the world who were documenting and preserving indigenous plant names. People for whom words and worlds are one. The question of how to save species is inseparable from how it is spoken and written, and who speaks and writes it.

I lean in to archival omissions and silences, strain to hear distant voices.[5]

In 2019 I find 60 images of extinct plants, 30 critically endangered, and 15 endangered plants and their names in 48 local languages.

I am working in archival gaps now, re-imagining documents, repurposing digitality and unfixing images. These acts disturb the herbarium order, challenge taxonomic principles and threaten established hierarchies of knowledge, including botany’s separation of nature from culture.

I conceal information too, suppressing digital layers that signify institutional exploitation and possession. I seek to visibilise through absence and erasure.

I have faith in images, not to show some pre-existing reality, but to generate different ones, ideas for the future that also expose the past. Archival images are not only about what is represented, but about what is forming, what is changing.

In 2022 I find 120 images of extinct plants, 80 critically endangered and 30 endangered plants, and match them to common names in 110 local languages.

Images cannot bring back extinct plants but they might help save endangered ones. They might be used as openings, to find and gather vernacular knowledge, to pressurise the boundaries and legacies of science.

These words, that I speak, are part of these images too. A lament for lost plants and lost voices, but also a reminder that in looking at the ghosts of the past we might save something for the future.

Acknowledgements and thanks to:

Hu Ai-Qun, Kew Gardens Herbarium

Magda Bou Dagher Kharrat,Mediterranean Fac. of European Forest Institute

Luana Calazans, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro

Asuncion Cano Echevarria, Univ. Nacional Mayorde San Marcos

Alison Copeland, Government of Bermuda

Sebsebe Demissew, Addis Ababa University

Anteneh Desta, Haramaya University

Roy Gereau, Missouri Botanical Garden

F.N. Gachathi, Kenya Forestry Research Institu

Sam Gon, Hawaii Nature Conservancy

Abdalla Ibrahim, University of Potsdam

Peris Kamau, National Museums of Kenya

Canisius Kayombo, Forest Training Institute, TanzaniaQuentin Luke, National Museum of Kenya

Itambo Malombe, National Museums of Kenya

Domingo Madulid, De La Salle University, Philippines

John Mbaluka Kimeu, Department of Biological Sciences, South Africa

D Narasimhan, Tamil Nadu Biodiversity Board

Melanie Medecilo-Guiang, Central Mindanao Univ.

Romana Oviedo Prieto, El Instituto de Ecologíay Sistemática

Alan Meerow

Raghavendra Rao, Indian National Science Academy

Mijoro Rakotoarinivio, Universite d’Antananarivo

Harish Singh, Botanical Survey of India

Robert Douglas Stone, University of KwaZulu-Natal

Marie Helene Weech, Kew Gardens

Blanca Leon, Museo de Historia Natural, Lima

[1] https://www.wired.com/story/timothy-morton-hyperobjects-all-the-way-down/?ref=transfer-orbit.ghost.io

[2] See Kathleen Guttierez essay Cycas wadei and Enduring White Space, in Empire and Environment, Confronting Ecological Ruination in the Asia–Pacific and the Americas, edited by Rina Garcia Chua, Heidi Hong, Jeffrey Santa Ana, and Xiaojing Zhou, University of Michigan Press, 2022.

[3] See Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, edited by Anna Tsing, Heather Swanson, Elaine Gen, Nils Bubandt, University of Minnesota Press, 2017 for a full exploration of this idea.

[4] Rose, Deborah Bird. 2011. Wild Dog Dreaming: Love and Extinction. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

[5] I am indebted to the Yasmine Eid-Sabbagh for this idea of ‘silences’ in archival images. See Extending Photography: the meta-medial/conversational layers of dematerialised photographs in Photography & Culture Special Issue, Volume 12 Issue 3in September 2019, edited by Tiffany Fairey and Liz Orton.