Horizontal Encounters with Mars

This text was read as a performed lecture with film/slides as part of the Photographers Gallery event Levels of Life: Photography, Imaging and the Vertical Perspective in June 2022, curated by Daniel . It was introduced by Daniel Alexander and Sara Knelman. Daniel introduced me as follows: “Liz has asked me to read this. She began to think about the idea of a photographic horizon many years ago. Then in 2019 she was diagnosed with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Spending a lot of time lying down, she now knows a lot more about the vertical world of trees, birds, ceilings, clouds and stars. She says: My body is a horizon.”

The horizon is not a place as such.

But comes into presence in vision and representation.

It’s a perceptual phenomenon that appears as a line

that joins and separates the earth and the sky

Without the horizon there would be no limit.

It marks an uncrossable space

always at a distance, elsewhere, and unreachable.

On Mars all our horizons are images.

And images are our horizons.

The journey to Mars starts in 1964 with Mariner 4, a US spacecraft, which made the first successful fly-by of the planet.

22 pictures were to be taken by an onboard TV camera and stored on a tape recorder. NASA described these images as close-ups though they were taken at distance of almost 10 thousand km from the surface of the planet.

The first image was a test image. It took six hours for the raw data to make the 34 million-mile transmission across space to earth.

Engineers on the ground grew impatient with waiting for what was to be the first photo of another planet taken from space.

They began to print the numerical data on ticker-tape as it arrived,

stapling it to the wall, strip by vertical strip.

The numbers corresponded to the position of the pixels they represented.

The engineers went to a local art shop and bought some coloured pastels, matching different colours to greyscale luminance.

It was drawing by numbers.

This was an anticipatory image, oriented towards a future machine image.

It is a fiction, shaped by material conditions and cultural histories.

A landscape drawing presented as scientific artefact.

The image is twice as wide as it should be, because of the width of the tickertape.

And it is upside down. The ground is in the top of the frame,

and the sky, the darkness of space, is at the bottom.

It’s an inverted horizon, and what appears to be a sunrise or sunset, is a myth, revealing more about operational practices than Mars itself.

Nevertheless, it was this pastel version, framed in wood and presented to the director the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at NASA, that was first released to the public, much to the annoyance of senior scientists.

The machine image, once processed was compared to the drawing and they were considered to be a good match.

After four days of waiting, 22 blurry images revealed a barren dusty planet covered in craters.

These images fuelled a demand for more images, necessitating further missions. At this point knowledge of Mars is purely visual.

In 1971 a Russian spacecraft, Mars 3 was the first to land on the surface of mars. Soon after touchdown It began transmitting an image but after 79 lines, the signal stopped, permanently. Nothing was released to the public, as the partial data was deemed to be valueless.

But then an image surfaced in the 1980s, during Glasnost.

Russian scientists continued to dismiss its importance.

It’s just a teleprint of a signal they said,

An image of noise.

Pre-photographic.

The black areas are empty, they are gaps in the data.

It is an index of a machine, not a place.

But the image began circulating anyway, mostly among Western scientists and space enthusiasts.

It had been heavily cropped and turned by 90 degrees.

It was claimed, without evidence, that the spaceship had fallen on its side.

Using this rotational logic the band of white became the horizon,

The foreground a rocky surface and the background a sky full of dust.

It’s a model of a landscape, with an imagined horizon

which, because it was a technical image,

was widely taken as a truth.

The image is no longer a representation of space, but space a representation of the image.

Soon after Mariner 9 completed the first orbit of Mars, capturing images of volcanoes and mountains three times the size of those on earth. As a flat cartographic image, it is difficult to interpret, so the horizon is made visible as a line underneath, grounding us and showing us the drama of its highs and lows.

In 1976 Viking 1 another US spacecraft became the first to transmit a complete image from the surface of mars.

There was an argument.

The head of imaging insisted that this first image was to be of the Lander’s foot on the ground.

This gives the best evidence of our mission’s success he said, and geological information in the event that we get no further images.

Other scientists in NASA disagreed. One said publicly,

‘If you were an explorer transported to an unknown terrain, would you first look down at your feet? No, you would look towards the horizon’

So a second photo came very quickly after, broadcast widely on TV.

With a greyish terrain and a blue sky.

But, it had been white balanced for conditions on earth, so

was quickly replaced by yet another image,

with a reddish terrain and pink sky.

All traces of the lander had been removed,

the image had been cropped from a square to a rectangle,

and corrected for an 8% tilt to straighten the horizon.

These adjustments help remodel the image

into a more familiar landscape photograph.

We have occupied this vantage point before.

The terrain is not that different from the American west, for example,

whose photographic past entwines images with domination,

using landscape to frame land as both pristine and profitable,

to naturalise its settlement and exploitation.

The horizon orients and stabilises us,

physically and culturally, as grounded beings.

It is a thread making planetary connections,

opening up and demarcating a visual field in front of us.

This is the horizon of perspectival histories

that gives us, its observers, a position, and a body,

making us centred rational subjects,

free to contemplate new territorial possibilities.

20 years later, in 1997, the first mobile camera, also American, called Sojouner, travelled 100 meters across the surface of Mars.

Its first image, a form of portrait looking back at the lander and its deflated parachute, is a document of its arrival. The curved horizon, the visible join in the middle of image, the vignetting, and the sunflare, all conditions of remote automated vision, were seen imperfections in need correction. So again this first image was quickly updated.

Some time later came the mosaics,

Digitally stitched from multiple frames and configured

to recover the stability and navigability of the ground through a levelled horizon.

The black parts a reference both to the computer screen and dark matter of space.

Even with their irregular edges and the clear signs of image processing,

they are still recognisably landscape photographs,

with enough spatial logic

for us to believe in them as representation of a place, a window onto a remote reality.

These images are acquisitive – if we want more territory, we add more images.

As if images can control what they represent.

Curisioity, again American, with 17 cameras, arrived in 2012 and is still sending us images today.

Curiosity’s first image was turned clockwise by 47 degrees, once again rescuing the horizon through a series of re-framings.

The fine dust that coated the camera’s lens just after landing became part of the image,

and might be seen as a mark of its authencity, but it was for many

a wasted photo opportunity,

as if a this was taken by a fully grounded photographer, and not a machine at a distance of 34 million miles.

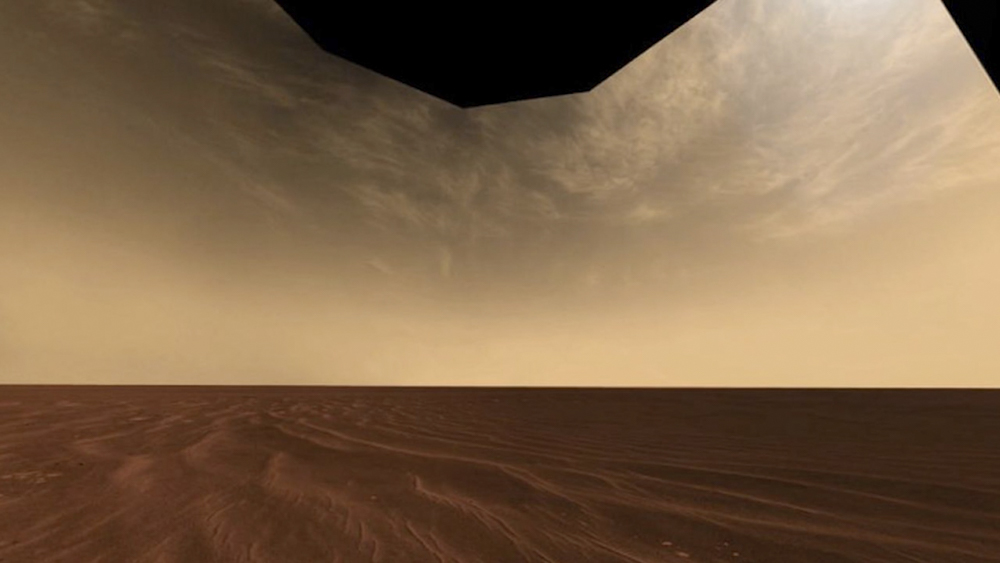

Later from Curiosity a photographic horizon so perfect

that it seems mathematically rather than organically straight,

the weight of the line pulling the sky out of shape,

exerting its force over the space in the image.

This is a scene re-arranged for a pivotal human subject,

as if the human eye is the ground of all seeing,

the still point that is both the picture’s origin and its conclusion.

The caption tells us this is record of a measurement of cloud activity,

which is another way of saying it is real.

It wasn’t long before curiosity captured a blue Martian sunset,

the most reproduced of all the planet’s images.

According to colour psychology blue is the colour of peace and happiness,

freedom and intuition,

imagination depth, trust and loyalty,

sincerity, serenity and stability,

wisdom, confidence, faith.

integrity and intelligence,

responsibility, commitment, professionalism, knowledge and power,

loneliness, loss and depression.

in the West blue is reportedly the favourite colour of men and conservatives.

The distant blue of the distant horizon of a distant planet - a container and an invitation, for all manner longings and desires.

It is as if Mars already belongs to us, and we are the universal and rightful owners of all its vantage points.

Making it legible and calculable and approachable.

Vision is detached from other bodily senses

preparing the ground as if we are all that we see.

Elon musk says ‘I have my sights on Mars.’

Just this week I heard a news report about its habitability, its prospects for future human settlement.

There were words like freedom, growth and opportunity.

It didn’t make much of the radiation, the sub-zero temperatures, the thin atmosphere, lack of oxygen and surface water, or the savage dust storms that can engulf the whole planet for months.

None of this is visible in the pictures, which are colonial vanguards for cosmic ambition, laying an optical ground.

Also silent are the geopolitical interests of governments and corporations.

So far this Space Race has been dominated by America but Russia, China, the EU, the United Arab Emirates and India are also now operational on and around Mars, generating more images.

200 miles away from Mars a high-resolution camera, called HIRISE, circulates in constant orbit, sending data to earth via the Deep Space Network, in 15 minutes.

One HiRISE image can contain 16,666 times as many bits as the Mariner images from the 1970s.

These images from above bring an end to the horizon, so that the ground on which we stood is our new field of vision. There are gullies, channels, craters, mountains and dunes, but without horizons there is no sense of scale, no fixed centre, and the images seem to have the force of an anonymous realm of otherness.

They are pure surface, so that we become adrift and directionless.

The unreachability of the horizon is replaced with the tension of facing the ground, or falling towards it.

The photos are like fragments of pink, grey and blue bodies: hairs, sinews, blotches, scars, pimples, scratches, spots, veins, and skin.

An anatomy of parts, spun out from the centre, detached from the whole. Without the line of the horizon to connect them, they become divided from each other.

What is this entangled topography, which confuses the distance between subject and object, observer and observed?

The HIRISE is known as the People’s Camera. It’s a web-based click-able, zoom-able, downloade-able image bank with 70,000 photos freely available without restrictions on use.

An automated image pipeline undertakes extensive processing, including binning, stretching, radiometric calibration, stitching, geometric projection, contrast augmentation, and colour interpretation. Each image product, as they are called, is then checked by a human.

And now there is a hook up with Google so it’s easier than ever to go to Mars from our laptops.

The images are primarily scientific documents for the study and calculation of the morphology of Mars, but the ones on display on the HIRISE website are heavily cropped, showing as little as 5% of the original raw file. These cuts abstract and aestheticise the ground, controlling the other through composition.

Though part of a network of relations between land, capital, technology and vision, these images float as detached media objects, without a clear source of authority. We participate in their circulation, sharing and reproducing them, creating new constellations and separating them further from their origins.

These fragments, which cause rapture and uncertainty, are part of a knowledge system expanding outwards into space.

They make a line from me towards infinity.

The old ground, stabilised by views of planetary horizons, is giving way.

We are no longer outside of images looking in but orbiting with images, catching glimpses as we pass by each other.

This ungrounding is part of a wider vertical reorientation between bodies, space and imaging technologies.

But while these images might uplift us, they make it harder to keep our sights on who or what is in control.